Modern Chinese religion is the co-joining of two separate but inseparable ancient religious traditions, Confucianism and Taoism, which are today considered two halves of the same spiritual whole. This article discusses these traditions and how they are interwoven into the fabric of Chinese society.

Chinese religion

Chinese religion has a long and complex spiritual tradition, with references to a great spiritual being referred to as “Lord-on-High,” dating back at least 2500 years. Complimenting this ethereal personified concept is the ancient idea of ch’i, an impersonal life-force encompassing two opposing but equal aspects, yin, and yang. From these concepts, two distinct religious traditions rose from China at approximately the same time—the sixth century BCE, which today are considered two halves of the same whole: Confucianism and Taoism. From the Eastern mindset, these two spiritual traditions represent the Yin and the Yang of the totality of Chinese religion.

Confucius and his revolutionary ideas

K’ung Fu-Tzu, known as Confucius to the ancient Greeks, lived during a period of social unrest called “The Warring States Period,” when feudalism, the reigning social structure of the time, did not foster a unified, harmonious society. Opposing conventional thought, Confucius proposed a solution to the wide-spread societal discord that greatly differed from the brutal advocating of force used by the so-called “Realists,” instead of fostering what he envisioned as a “deliberate tradition” that would put Asian society into harmony. The elements of this deliberate tradition are what Confucius termed Jen, li, Chun Tzu, te, and wen.

Jen refers to the essential nature of humanity, which is social. The Chinese character for Jen is a combination of the characters for “two” and “person,” thus Jen suggests relationship; the proper attitude of relationship. It is often translated as “human heartedness.”

Li is the notion of right conduct in the five basic relationships essential for a stable society, including, parent and offspring, husband and wife, and older friend and younger friend. Chun Tzu is the person who can embody Jen by practicing li.

Te is power, but not physical power. It is more the power of moral and social example.

Wen is sometimes translated as “arts of peace.” A harmonious society, that is aware of the mutual relationships and rituals necessary to sustain those behaviors, will be a society that nurtures the arts, specifically the arts that help shape virtue.

Although Confucianism is sometimes considered an ethical or philosophical social system rather than a religion, its emphasis on the irreducible social element in human affairs cannot be understated, not its historic effectiveness.

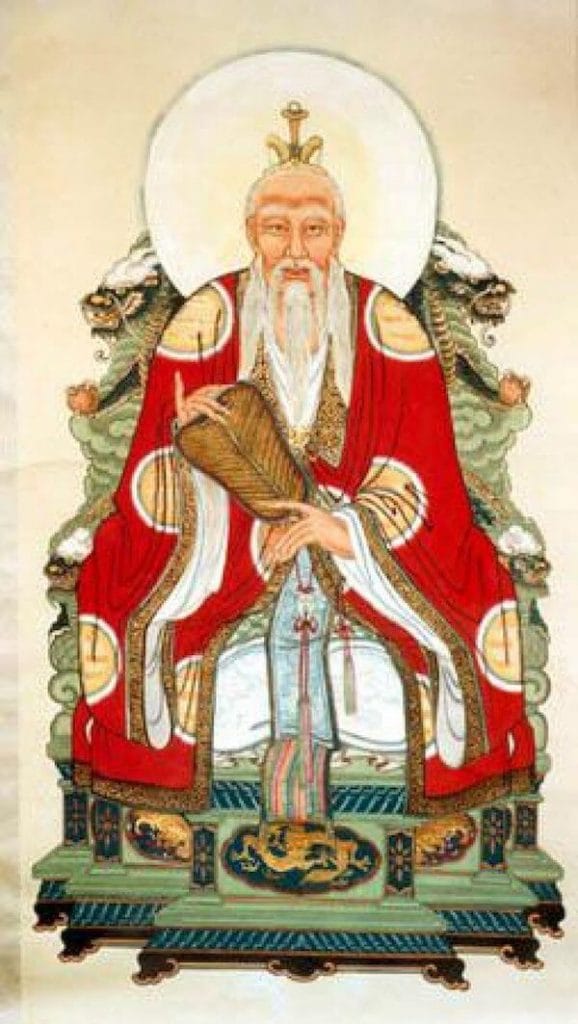

Lao-Tzu and Taoism

According to tradition, at approximately the same time that Confucius was teaching his ideas, another aspect of Chinese religion—Taoism—was taking form. Lao-tzu, simply known as “the old man” in the Chinese tradition, compiled the classic text, the Tao Te Ching, the Way, and its Power. Although there are institutional forms of Taoism that emphasize the longevity of an individual’s life, the Tao Te Ching remains the classic statement of Taoist ideals.

The first line of the Tao is perhaps the most well-known: “The name that can be named is not the true name.” This conceptualized the idea that the ultimate, whenever it is described, is not the ultimate once described. The Tao, the way of ultimate reality, is named, but Taoism recognizes that mere language cannot contain the ultimate. So the Tao Te Ching, necessarily, uses metaphor and poetry to help readers understand the flow of the Tao.

For example, it is often said that the best way, perhaps, to be in harmony with the ultimate way is to remain silent, to remain quiet, and to refrain from action, the notion of wu-Wei, “action-less action.” Difficult to understand (especially for Westerners), a metaphor from the Tao Te Ching hopes to clarify: “What is the best way to get a container of muddy water to become clear? Do nothing. Let the container sit and the dirt and mud will eventually settle to the bottom and the water will be clear.”

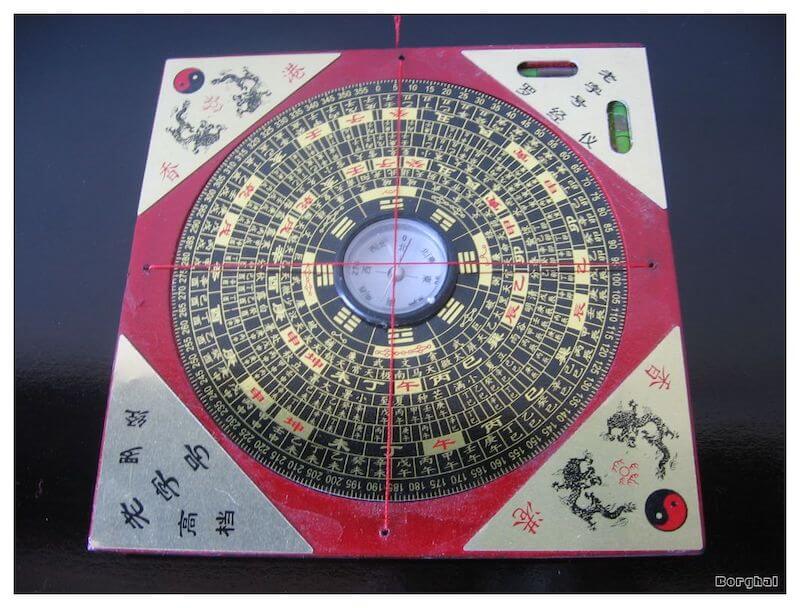

Feng-shui

The goal of being in balance with the Tao, the ultimate force of the universe, is the goal of feng-shui, an increasingly popular practice in the West where one becomes aware of the flow of ch’i, the vital energy, within a dwelling or landscape, repositioning objects at their optimal placement to allow the flow of ch’i to move uninterrupted, thus promoting harmony.

T’ai-chi ch’uan

Another form of energy practice is T’ai-chi ch’uan, developed in the eighteenth century as a martial art form but practiced today in the West as a way of becoming one with the flow of yin and yang within an individual, and often used as a meditative practice.

Confucianism and Taoism

Either in its classic formulation or contemporary manifestations, Taoism seeks harmony and balance, in the universe and an individual’s life. Coupled with Confucianism’s goal of harmony in society (and once again yin and yang), Taoism and Confucianism form the complementary dualism that is Chinese religion.