Updated: 27 February 2021

“The History, The Executioners and the Executed”

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century and demolished in 1777. The prison was extended and rebuilt many times, and remained in use for over 700 years, from 1188 to 1902.

Newgate Prison History

“Hell itself, in comparison, cannot be such a place” suggested an unfortunate resident of Newgate Prison in 1662. Kelly Grovier’s pacy account of the institution from its founding in 1188 by Henry II through its renovation by Richard Whittington in the 15th century, its various reconstructions following fires, to demolition in 1902 examines the horror of the place with relish: “The mingled stench of disease and feces and the cacophonous din of wailing and screeching in the maze of unventilated wards was unutterably horrifying.”

Burned Down in Riots 1780

The prison was attacked and burnt down during the Gordon riots in 1780 and, while it did not loom so large in the minds of the locals as did the Bastille for Parisians sacked only a few years later – it was a potent symbol. It would be possible to write its history by simply looking at the novels, plays, pamphlets, images, and ballads that it has inspired.

Ben Jonson spent time there, as did Christopher Marlowe, who included the prison into his later plays; Daniel Defoe wrote biographies of two celebrated inmates, before fictionalizing the prison in Moll Flanders; John Gay’s savagely satirical The Beggar’s Opera was initially called “The Newgate Opera”; William Hogarth and Gustave Doré illustrated the miserable place; and Dickens returned to the scene near-obsessively, including it almost as an extra character in Nicholas Nickleby and Oliver Twist.

Yet, as Grovier makes clear, Newgate was also a place of performance and self-fashioning, where prisoners could become celebrities for a brief time. Those who spent time in Newgate’s various manifestations (the jail was rebuilt at least three times) include Jack Shephard, a serial absconder, who received more than a thousand visitors when he was rearrested after his fourth escape, and Claude Duval, whose execution in 1670 was, according to a contemporary account, attended by “a great company of ladies…their cheeks blubbered with tears”.

These examples are far from unusual. Plunkett and MacLaine, Anne Askew, Captain Kidd, James Hind, Wat Tyler and Elizabeth Brownrigg all spent time in Newgate. The accounts of their deeds – in pamphlet form, in pulp biographies, and the massively popular Newgate Calendar – took hold in the public imagination and created a demand that stirred the writings of Defoe and Dickens. The prison also contributed to the developing cultural importance and visibility of crime, with ballads, woodcuts and songs representing the famed criminals to the populace.

The prison is a repository of hundreds of stories and Grovier retells them with some vim. The source materials allow him to encompass all manner of subjects: from the reforming work of Samuel Johnson, Elizabeth Fry and Jeremy Bentham, to accounts of the prison as an institution, with its economy, vocabulary (“Newgate Cant”) and social organisation. Grovier’s treatment of the material organisation of the place is excellent, ranging from its physical layout to the design of the gallows, from the class implications of the renovations to the role of the various corrupt officers in administering “justice” (“Garnish, Captain, garnish” shouts Gay’s keeper Lockit, asking for a fee to make Macheath’s stay more comfortable).

These stories are not new – Stephen Halliday’s Newgate: London’s Prototype of Hell (2006) mined a similar seam of sensation and social history – but they remain gripping. Newgate’s role in the evolution of London, in the creation of crime in the public imagination, in the development of the concept of the prison, is unmatched, and Grovier relates it compellingly.

When Did it Become a Prison?

It is not possible to determine when Newgate first became a prison or when exactly the new gatehouse itself was originally built. Newgate was to be London’s 5th gate into the city. Reliable records are going back to 1218 of them being used to housing criminals. It was finally demolished in 1904 having been rebuilt at least twice along the way.

A new prison at Newgate was begun in 1770 and proceeded slowly. Before it could be finished, the building was badly damaged by fire during the Gordon riots of 1780 and it was not finally completed until 1785. This building was then used in that form until 1856 when it was remodelled internally to reflect the new perceptions of what a prison should be like. London’s Millbank and Pentonville prisons had been designed to be the first modern prison and to practice the new “penitentiary system.” This rebuild was very short-lived as the building was very badly damaged, again by fire in 1877, and had to be largely rebuilt.

As a result of the Prisons Act of 1877, Newgate ceased to be an ordinary prison in 1882 and was used only for those awaiting trial and prisoners sentenced to death awaiting execution. Newgate had a great advantage, from the authorities’ point of view at least, of being next door to the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey) which was the trial venue for all of London’s most serious criminals. It saved the cost and security risk of transporting prisoners by horse-drawn van from other prisons for their trial.

The Central Criminal Court Act of 1856 permitted prisoners from anywhere in the country accused of a very serious offence to be tried at the Old Bailey. The Act was passed to allow for poisoner, William Palmer (from Rugeley in Staffordshire), to get a fair trial free from local prejudice. The advent of an efficient railway system had made it possible to transport prisoners over considerable distances. Palmer was returned to Stafford prison for his execution. Similarly, Maria and Frederick Manning and Kate Webster were kept at Newgate during their trials and then returned to the Surrey county gaol at Horsemonger Lane for execution.

Newgate closed for good in late May 1902 so that the new Central Criminal Court which opened in 1907 (always known as the Old Bailey) could be built on the site. The Debtor’s door through which the condemned prisoners exited in the days of public hangings and the site of the gallows at that time are marked. Up to 1877, in its several incarnations, Newgate was the principal prison for London and Middlesex and housed all manner of prisoners of both sexes, including those remanded in custody and prisoners awaiting transportation or execution and those imprisoned for debt. When Newgate closed, its male prisoners and indeed its gallows were transferred to Pentonville while the female prisoners were moved to Holloway prison, which had been recently renovated and turned into London’s first women’s prison.

Appalling Conditions in Early 19th Century

Conditions in Newgate in the early part of the 19th century were appalling and led to great efforts by early prison reformers such as John Howard and Elizabeth Fry to improve things. Elizabeth Fry was deeply shocked by the conditions that women were detained under, in the Female Quarter as the women’s area was known, when she visited the prison in 1816. She found the place crowded with half-naked women and their children. The women were typically waiting for transfer to the prison ships that would take them to the Colonies. Women were brought to Newgate from county prisons in the south of England to await transportation and kept there for weeks or months until a ship was available.

Many of the ordinary women prisoners were drunk, due to the availability of cheap gin, and some were deranged. They were kept in leg irons if they could not afford to pay the Keeper of Newgate for “easement.” Fry formed an “Association for the improvement of the female prisoners in Newgate” and as part of that, set up a school within the prison for the younger children in 1817.

The following year, she gave evidence to the Parliamentary Committee on her findings. She was able to get a proper Matron appointed to look after the women in 1817 and conditions slowly improved. Prisoners under sentence of death were kept shackled and apart from other prisoners and in the case of murderers, fed on bread and water for the final 2-3 days of their miserable lives before meeting the hangman. Their only permitted visitors were the prison staff and the Ordinary (prison chaplain).

Conditions improved after 1834, condemned prisoners spending around 2-3 weeks awaiting execution after the law was changed to allow three clear Sundays to pass before they were hanged. They were no longer kept in irons and were given better food than the ordinary prisoners. They were also permitted visits by their families and friends. As London was the crime capital of England, so it was that Newgate was the execution capital and between 1783 and 1902, a total of 1,169 people were put to death there or nearby (12 or 13 hangings being carried out at other locations before 1834). The total comprised of 1,120 men and 49 women. The last remnants of the “Bloody Code” as it was known remained in force up to 1836. Over 200 felonies were punishable by death in 1800, although in practice people were only executed for about 20 of them.

See the analysis below. Those convicted of the more minor ones, although sentenced to death, typically had their punishment reduced to transportation. The concept of imprisonment as a punishment only really came in after 1840. Transportation ended around 1888.

Public executions were carried outside Newgate in the lane known as the Old Bailey from the 9th of December 1783 (following the ending of hangings at Tyburn). It is unclear where the gallows was erected before 1809 – contemporary reports talking of “outside Newgate” and “in the Old Bailey.” After 1809, almost all hangings took place on the portable gallows in front of the Debtors’ Door and continued here up to the 25th of May 1868, when Michael Barrett became the last to hang for the Clerkenwell bomb outrage that killed seven people. Three women were the Old Bailey, for the crime of coin which was deemed to be high treason. They were Phoebe Harris, Margaret Sullivan and Catherine Murphy. In all three cases, they were first hanged until they were dead and then their bodies burnt.

Similarly, the Cato Street conspirators who had also been convicted of high treason were sentenced to be there (the male punishment for high treason), but in fact, were hanged and then beheaded. There were to be 567 public hangings, including those of 25 women, between January 1800 and May 1868. These drew huge crowds, especially if one of the prisoners was notorious. From 1752 to 1832, the bodies of those executed for murder were taken to Surgeon’s Hall in the Old Bailey where they were publicly anatomised. Up to 1834, the bodies of persons executed for crimes other than murder could be returned to relatives for a fee.

There were only two confirmed executions at Newgate in the years 1834-1836, those of John Smith and James Pratt, who were hanged for buggery on the 27th of November 1835. After 1836, only murderers were to be hanged at Newgate and their bodies were buried in unmarked graves within the walls. Ninety-nine men and eight women were to suffer from this crime between 1837 and 1902. Of this total, 58 men and five women were executed in private between the 8th of September 1868 and the 6th of May 1902 when George Wolfe became the last person to be executed here. There were four double hangings, a treble and a quadruple hanging during this period.

Edward Dennis Official Executioner 1771 – 1786

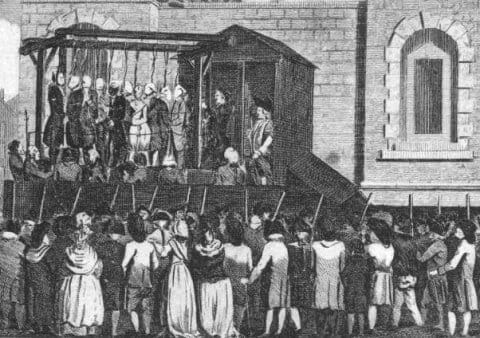

From around 1771 to September 1786, when he died, Edward Dennis was the official executioner and carried out 201 hangings and the three burnings at Newgate. He had previously officiated at Tyburn from 1771. On Tuesday, the 9th of December 1783, he and William Brunskill hanged nine men and one woman (Frances Warren) side by side on the “New Drop” at Newgate’s first execution. Note that they all have white nightcaps drawn over their heads. Sessions, as trials at the Old Bailey were known at that time, were held eight times a year by then and it was normal to sentence those found guilty of crimes other than murder in groups at the end of the trial day. Murderers were sentenced at the end of their trials.

Those sentenced to death for felony and not “respited” (commuted to transportation) were also hanged in groups – men and women together. Multiple executions were the norm at this time and took place normally around six weeks after the Sessions finished and the Recorder of the Old Bailey had prepared and presented his report indicating which prisoners were recommended for reprieve and which were to be executed.

From July 1752 onwards, murderers had to be hanged within two days of their sentence, unless this would have been a Sunday, which meant that they were typically hanged on a Monday and therefore usually separately from ordinary felons, this day continuing to be used at Newgate for murderers up to 1880.

Ordinary criminals could be hanged on any day of the week, Wednesdays being the most common one. Prisoners were led from the “Condemned hold” into the Press yard where their leg irons were removed and their wrists and arms tied. They were attended by the Ordinary and when they had all been prepared, were led across the yard to the Lodge and out through the Debtor’s Door and up a short flight of steps onto the gallows. Dennis hanged 95 men and one woman between February and December of 1785 at Newgate, with 20 men being hanged on one day alone (Wednesday, the 2nd of February).

Dennis was often assisted at these marathons by the man who was to become his successor, William Brunskill, who went on to hang an amazing 537 people outside Newgate as principal hangman. He also executed a further 68 at Horsemonger Lane Gaol in the County of Surrey between 1800 (when it opened) and 1814. John Langley took over from him in 1814 and hanged 37 men and three women in his three years in office, including Eliza Fenning. He died in April 1817 and was succeeded by James Botting who was known as “Jemmy”. Botting hanged 42 men and two women during his two-year tenure, during which in 1818, shoplifting was removed from the list of capital crimes at the instigation of Sir Samuel Romilly.

The gallows used by Dennis, Brunskill and Botting had two parallel beams from which a maximum of a dozen criminals could be hanged at once. The platform was 10 feet long by 8 feet wide and was released by moving the lever or “pin” acting on a drawbar under the drop. The condemned were given a drop of between one and two feet so death was hardly ever “instantaneous.” On one occasion, presumably because the mechanism had failed a simple beam and cart was used to get the prisoners suspended, as had been done at Tyburn. This was for the execution of Methuselah Spalding in February 1804. This lapse attracted severe criticism in the press. In July 1819, James Foxen assumed the position having previously assisted Botting, and hanged 207 men and six women over the next 11 years.

The five Cato Street conspirators became the last to suffer hanging and beheading on Monday, May 1st, 1820, for conspiring to murder several members of the Cabinet. Foxen was assisted by Thomas Cheshire for this high profile execution and an unnamed and secret person who cut off the traitor’s heads. Given their crime, their bodies were the property of the Crown and were buried within Newgate

Thomas Cheshire The Principal of Quadruple Hanging

Thomas Cheshire, or Old Cheese as he was known, officiated as principal at a quadruple hanging on the 24th of March 1829 of three highway robbers and one man convicted of stealing in a dwelling house. These were Cheshire’s only executions as principal at Newgate. The gallows was now modified, from then on, having only one beam with a capacity for six persons. In 1820, there were 42 executions on seven “hanging days” at Newgate, all carried out by James Foxen. Not one of these was for murder. Twelve were for “uttering” forged notes, 12 for robbery or burglary, and five for highway robbery. At this time, murderers, rapists, arsonists, forgers, coiners and highwaymen were virtually always executed and were seldom offered transportation.

The largest multiple executions in 1820 was that of eight men on the 11th of December and the smallest was of three men on the 24th of October. Sarah Price was the only woman to suffer in 1820, alongside six men, for “uttering” forged banknotes or coins on the 5th of December.

On the eve of hanging, the portable New Drop gallows was brought out by a team of horses and placed in front of the Debtor’s Door of Newgate. Large crowds gathered around it and it would be guarded by soldiers with pikes. Wealthy people could pay as much as £10 for a seat in a window overlooking the gallows at the hanging of a notorious criminal. At around 7.30 a.m., the condemned prisoners were led from their cells into the Press Yard where the Sheriff and the Ordinary (prison chaplain) would meet them. Their leg irons were removed by the prison blacksmith and Foxen and his assistant would bind their wrists in front of them with cord and also place a cord round their body and arms at the elbows. White nightcaps were placed on their heads. The prisoners would now be led across the Yard to the Lodge and then out through the Debtor’s Door where they would climb the steps up to the gallows.

There would be shouts of “hats off” in the crowd. This was not out of respect for those about to die, but rather because the people further back demanded those at the front remove their hats so as not to obscure their view. Once assembled on the drop, Foxen would put the nooses around their necks while they prayed with the Ordinary. Female prisoners might have their dress bound around their legs for the sake of decency but the men’s legs were left free.

When the prayers had finished, the Under Sheriff gave the signal and the hangman moved the lever, which was connected to a drawbar under the trap, and caused it to fall with a loud crash, the prisoners dropping 12-18 inches and usually writhing and struggling for some seconds before relaxing and becoming still. If their bodies continued to struggle, the hangman, unseen by the crowd within the box below the drop, would grasp their legs and swing on them so adding his weight to theirs and thus ending their sufferings sooner. The dangling bodies would be left hanging for an hour before being either returned to their relatives or, in the case of murderers, sent for dissection. Execution Broadsides were usually sold among the crowd, purporting to give the last confessions of the condemned. These were like tabloid newspapers of the day and were often a total fabrication. As they were printed before the execution, they were quite often unused if a reprieve was granted after printing, not an uncommon occurrence at that time. They would show a stylised woodcut picture of the hanging and had details of the crime.

William Calcraft took over from Foxen as Executioner March 1829

Ordinary newspapers were very few at this time and relatively very expensive so were only read by the wealthy. William Calcraft took over from Foxen in March of 1829 and carried out 86 executions here, his first job being the hanging of the hated child murderer, Ester Hibner, on the 13th of that month. Before taking up the position, he had sold pies at hangings and had got to know Foxen and Cheshire. Calcraft was to go on to hang a total of 86 people, including six women at Newgate before he was retired in 1872. One of his most famous cases was Francis Courvoisier, who had murdered his master, Lord William Russell.

Another was Britain’s first railway murderer, Franz Muller, who he publicly hanged on the 14th of November 1864 for killing Mr Thomas Briggs. Calcraft carried out both the last public hanging at Newgate (Michael Barrett) and the first private one four months later, that of Alexander Mackay on the 8th of September 1868. Mackay was 18 years old and had been convicted of the murder of Emma Goldsmith, his employer. The gallows had been erected in an enclosed yard near the Chapel, and the execution was attended by representatives of the Press.

A little before 9.00 a.m., Mackay was led into the yard supported by the Chaplain, the Rev. Mr Jones, and ascended the steps onto the platform where he joined in with Mr Jones’ prayers. Calcraft pulled the lever and Mackay dropped a few inches and took several minutes to become still, according to contemporary reports. George Smith assisted Calcraft at this hanging. The black flag was raised over the prison after the trap had opened. His body was left hanging for an hour before being taken down and prepared for the formal inquest, which took place that afternoon. Mackay was then buried within the prison in an unmarked grave.

Like his predecessors, Calcraft was also responsible for carrying out floggings at Newgate and was paid a salary with additional monies for hangings and floggings. With the advent of a comprehensive railway network, he was able to work over most of the country in his later years and became Britain’s principal hangman. During Calcraft’s time, the number of executions fell dramatically (see below). Proper condemned cells had been constructed in Newgate during the early 1830s, created by knocking two ordinary cells into one thus ending the use of the appalling “Condemned Hold” which was little more than a dark, feted dungeon. From 1848, condemned prisoners were guarded round the clock by two or three warders to prevent suicide. They took their exercise in a covered walkway known as Birdcage Walk or Dead Man’s Walk, their cell being at the far end of this

William Marwood: Seventeen Executions

William Marwood was Britain’s next hangman and officiated at 17 executions, including that of 45 years old for killing her grandson. Assisted by George Incher, he hanged the four Lennie Mutineers for murder and mutiny on the 23rd of May 1876 in Newgate’s only quadruple private execution. This hanging was widely reported in the press. In 1881, a purpose-built execution shed containing new gallows was erected in one of the yards. The lower half doors were closed once the prisoner and other officials had entered and all witnesses saw was the prisoner disappear and the taught rope.

This facility remained in use until closure in 1902, the gallows being then moved to Pentonville prison and first used there for the execution of John MacDonald on the 30th of September 1902. You can see the metal bracket and chain hanging from the centre of the beam. Up to four brackets could be set up for multiple hangings. The lever is behind the right hand upright and there are pulleys for raising the trapdoors on each upright. A ladder is in the foreground leaning against the wall.

Bartholomew Bins carried out one hanging after Marwood, that of Patrick O’Donnell, before handing it over to James Berry who performed 12 executions here between 1884 and 1890. Berry was to hang Mary Eleanor Wheeler in 1890. He was replaced by James Billington who hanged 24 men and three women up to 1901, including Louisa Masset, the first person to be executed in Britain in the 20th century. He also executed the infamous baby farmer, Amelia Dyer who at 57, became the oldest woman to be hanged in modern times. Another of his famous customers was Thomas Neill Cream who, in December 1892, standing hooded and noosed on the trap said, “I am Jack the…. “ just as the drop fell. In reality, he could not have been Jack the Ripper. Billington carried out the last triple execution at Newgate when he hanged Henry Fowler, Albert Milsom and William Seaman (for two different murders) on the 9th of June 1896. The last hanging at Newgate was carried out by Billington’s son, William, on the 6th of May 1902. The prisoner was 21 years old George Wolfe, who had beaten and stabbed his girlfriend, Charlotte Cheeseman, to death.

Analysis of Executions between 1783 and 1902

Analysis of executions between 1783 and 1902 and the crimes for which people were put to death

1783-1799

559 people were put to death in this short period of just over 16 years, an average of 35 per year. 539 men and 17 women were hanged for a wide variety of crimes and 3 women were burnt for coining. (Women accounting for 3.6% of the executions) (A small number of these executions took place at or near where the crime was committed.)

1800-1899

There were 621 hangings at Newgate of which 30 were of women (4.8%), 543 were in public including those of 24 women. During this period in London, a further 23 men were hanged at Execution Dock at Wapping under Admiralty jurisdiction between 1802 and 1830.

1800-1833

There were 521 executions, all by hanging in public, comprising 499 men and 22 women. Only 44 of these executions were for murder, the rest being for various other felonies, particularly burglary and forgery. See the analysis below.

1835

Just two executions took place at Newgate when John Smith and John Pratt became the last to hang for sodomy in England on the 27th of November of this year.

1834, 1836 & 1838

No executions at all at Newgate, possibly for political reasons, as the laws had changed dramatically in the previous two to three years.

1837-1868 (public hangings)

A further 42 men and three women were hanged in public up to the 25th of May 1868, all for murder (including five men who were executed for murder and piracy – “The Flowery Land” pirates.)

1868-1899 (private hangings)

51 men and three women were executed for murder, including 4 men for murder and mutiny on a ship called the “Lennie” (the Lennie Mutineers).

1900-1902. Seven men and two women were hanged for murder in the 20th century before the closure of Newgate.